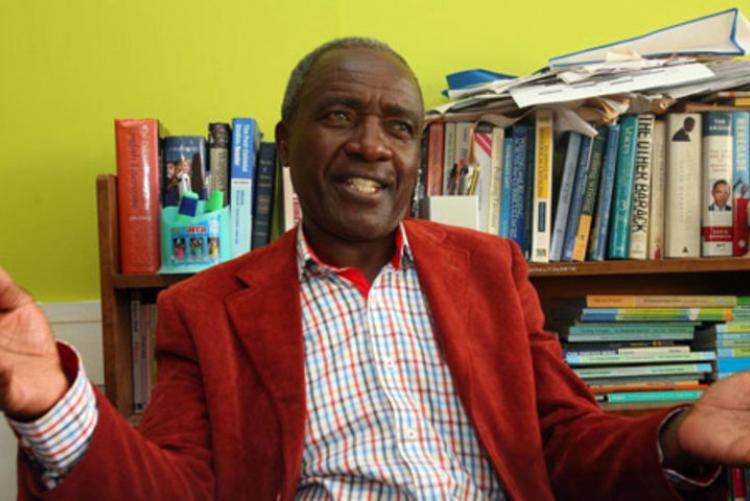

Prof. Henry Indagasi is as old as the University of Nairobi. He joined the department of Literature in 1970 and served as Chair of Department in 1988. In a webinar organized by the department of literature on 25th November, 2020, no one could have been better placed to tell the Department of literature’s story than Prof. Indangasi. The literary scholar went down the memory lane in an exciting presentation titled, “The Department of Literature at 50: The facts and the Fabrications.” Below is his story.

Ngugi wa Thiongo’s Famous Letter

In 1995 Carol Sicherman, American Scholar and author of the book, Ngugi wa Thiong'o, the making of a rebel came to the University of Nairobi. Sicherman had applied for and given a grant by her university to sort out a research problem concerning Ngugi wa Thiongo. Ngugi wa Thiongo published this letter which was co-uthored with Taban Lo Liyong and Owuor Anyumba, requesting the University of Nairobi to abolish the English department and replace it with the department of literature.

Sicherman told me when she came to the department, (I was chair of the department at the time) that Ngugi did not publish the reply to his letter from the relevant authorities. “I came via the UK and spoke to the Professors who were here but they all advised me to come and check with the Guinea pigs. They told me, you are one of them and as I recollect when she uttered the words guinea pigs I saw an Ironic smile on her face. “So my research agenda is to find out if there was a reply to the famous letter and of course the contents of the response.” She said. I figured I would have to go back to the senate documents of late 1960s. According to our statues, senate is the organ that discusses and approves academic programs and creation of new departments but then I wasn’t sure whether or not there were any ethical issues concerning an outsider who wanted to dig into our official archives. So I called Prof. Francis Gichaga the then Vice Chancellor to inquire about the issue. “Our senate minutes are public documents, we have nothing to hide and your friend should feel free to look at them.” Gichaga told me.

American Researchers consider it unethical to pay informants so when I offered to read through those dusty old minutes I knew I was going to work for free. We searched and searched and searched and in the end we found nothing. The legendary letter never reached the senate and was therefore never discussed. And come to think of it, if the university administration had reacted to the letter and accordingly informed the authors, Ngugi would have published the reply after all he did that with the back and forth correspondence with the institution upon his release from detention and that was when he was asking to have his job back. But as I was flipping through the records, I stumbled on a letter of the then chair of the department about Ngugi’s application for a teaching job. The letter was dated 1968 and in it the chair was requesting the British council to assist in the evaluation of Ngugis application. The council suggested the name of Prof. Keelam as an assessor and Keelam was a specialist on African literature who was teaching in Canada. Keelam recommended Ngugi for the job and the novelist was eventually hired as a special lecturer. The issue was that Ngugi had apparently been sponsored by the British council to pursue a Master’s degree at the University of leeds but he had come back without this qualification and according to a research Evan Mwangi did for his doctorate, Ngugi’s Master’s thesis had been rejected. Owuor Anyumba appeared to have suffered a similar fate. His CV states that he obtained a master’s degree from Cambridge university but he didn’t collect the certificate. I personally doubted this claim. Why wouldn’t you even take a loan to fly to the UK to pick up such an important document? Besides what prevented Cambridge University from mailing the certificate to their student. I submitted my own PhD dissertation to UC Santa Cruz in 1979 and they mailed the certificate to me in 1980. I showed it to Mr. Anyumba who was my boss at the time. Tabaan Lo Liyong had graduated with an MA in creative writing from the University of IOWA in the USA, he was therefore not in the mainstream literary scholarship. The point I want to make is that these three gentlemen must have been considered marginally qualified to teach in the University. Two were BA holders and the third had an MA in creative writing besides in 1968, they were newly employed, their desire to overhaul an academic curriculum must have appeared presumptuous and impertinent to the authorities of the time. I know about the cult of personality that has been created around Ngugi wa Thiongo. I also know that a more colorful personality was created. But let us for a moment do some critical thinking. In an institution with many PhD holders these three gentlemen must have wrestled identity issues, so we ask what was the motivation behind their literary activism? Was it a genuine and sincere desire to reform a curriculum or was it a compensatory or self-serving effort to stake a claim in the academic cosmos. They sought to abolish the English department and replace it the department of literature but given that English had long before become a world language, the idea of teaching literature in English and English translation rather than English literature had already been institutionalized.

For my Cambridge school certificate in 1967, one of my set books was Chinua Achebes, Things Fall Apart. As for my Cambridge higher school certificate in 1969, three of the set-books were outside the realm of English literature, Bartlett Breaks, Galileo lane and Camara lies the legends of the King. Brex play was a translation from German lyas novel was translated from French so when these three gentlemen fighting a battle that had already been won.

The Policy of Africanization

In 1968 the ministry of education headed dr Julius Viconochiano had already started implementing the policy of Africanization. If you read the newspapers of the time, you will find that Keanu’s detractors called the policy a decolonization. With that as it may, the ministry Africanized teaching positions in high schools including headships and by the early 1970’s this policy had reached the University of Nairobi, by 1973, the year I graduated ,nearly all our British lecturers had gone back to their country. Again, we ask the question; given that Africanization was the official policy of the Kenya government, and contrary to the tone of the letter in question, wasn’t this author simply swimming with the current rather than against it? If you excuse the cliché. Was it not cashing in on a policy that favored them? The department I joined in 1970 was not called the English Department. It was called the Department of Literature, most of the lecturers were Wazungus with Prof. Andrew as the chair. Taban Lo Liyong had joined the department having transferred from the Institute of African Studies and although we had courses such as the African Novel, Modern African poetry and oral literature, the majority of the offerings for single majors belonged to European or World literature like the Class novel, classic poetry, development of drama , theory of literature and stylistics, Shakespeare and Tolstoy, and their contemporaries. The previous year, Ngugi had resigned reportedly over the issues of academic freedom, the refusal of the university to allow opposition leader Oginga Odinga to deliver a public lecture at the institution but he came back in 1972 when I was doing my third year, as we saw it then, two related departments had been established , the department of literature with a mandate to teach literature in three languages, English, French and Kiswahili and the department of linguistics and African languages, the Sub department of French was housed under the department of literature but literature in Kiswahili never took off and this program was eventually appropriated by the department of linguistics and African languages. Maybe, the English department had been quietly abolished but there is no evidence that this was in response to the letter written by Ngugi, Taban and Anyumba.

In 1973, the year I graduated, the Wazungu were leaving, Ngugi wa Thiongo took over from Andrew but this transition happened after I had left. The change in the Curriculum, which many scholars talk about was as result of the conference on the teaching of literature that was held at Nairobi school in 1974. That was the same year I went to America on an exchange program called the University of California education abroad program but I was told that in his new role as the chair of the department Ngugi was the organizer of the event. On the positive side, this conference affirmed the education principal of moving from the known to the Unknown. African literature was accorded a central place in the syllabus but from the point of view of literature as an institution, the results of this meeting were calamitous, the age-old idea that good literature speaks to our common humanity went out the window instead literary works were to be taught from the perspective of how they related to Africa and Africans so we had concentric circles. African literature, literature of the African diaspora, literature of the rest of the world. The fact that Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina or Murasaki’s Tale of Genji tell the human story and resonate with the entire species of Homo sapiens was of no consequence to the participants. Black Aesthetics was introduced was introduced as a core course, in the course decription no attempt was made to define the concept of Hispanics instead the focus was on the suffering of black people in the struggle against institutions of self-slavery and colonialism. And I don’t know whether those who designed this course thought there was brown aesthetics, yellow aesthetics and white aesthetics. Whatever the case, the notion of the universal in literature was roundly rejected. The discipline became the face of African Nationalism.